Yuck! TARR on Your Heels?

go.ncsu.edu/readext?784076

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

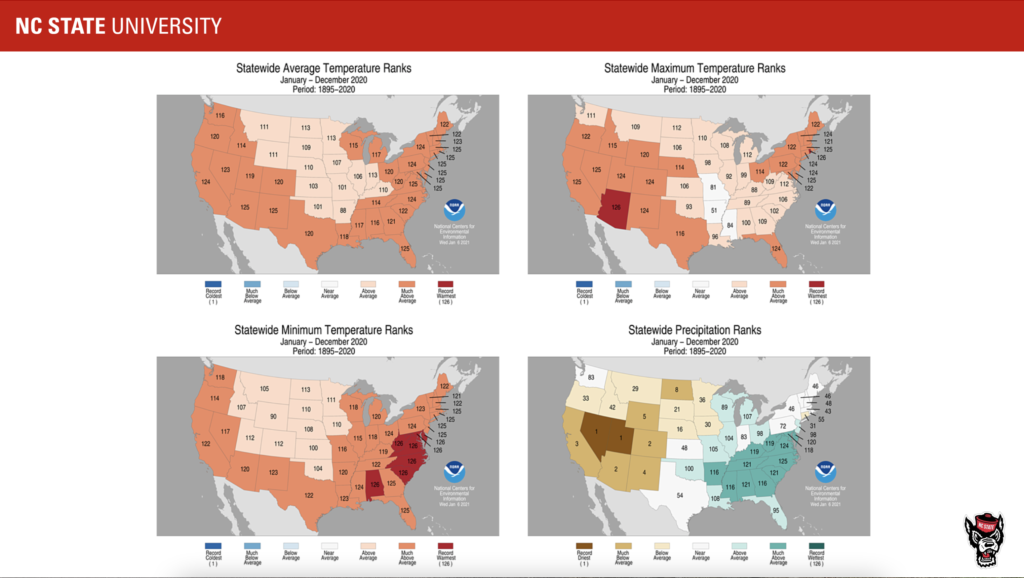

Collapse ▲Last fall was conducive for take-all root rot (TARR) in ultradwarf bermudagrass putting greens. There were substantial rain events in the fall which likely limited residual of fungicides as well. So even strong TARR fungicide programs could fail after the conditions that occurred last fall and through the winter. At least in NC, we were 2/100ths of an inch from record rainfall during the meteorological winter (December, January, and February). This probably further exacerbated any TARR damage that occurred last fall. Plus, Pythium species could also invade roots that were previously affected by TARR.

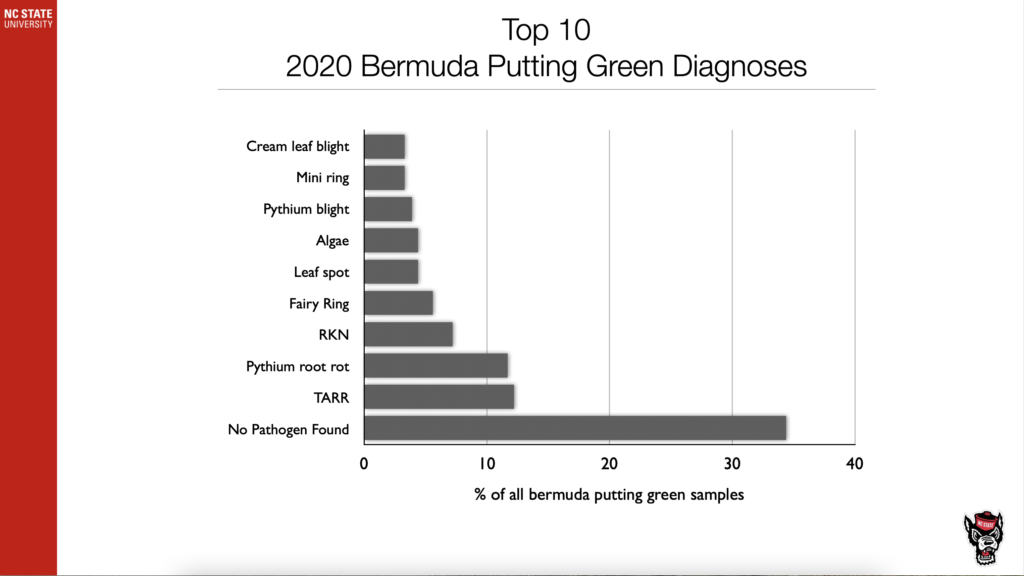

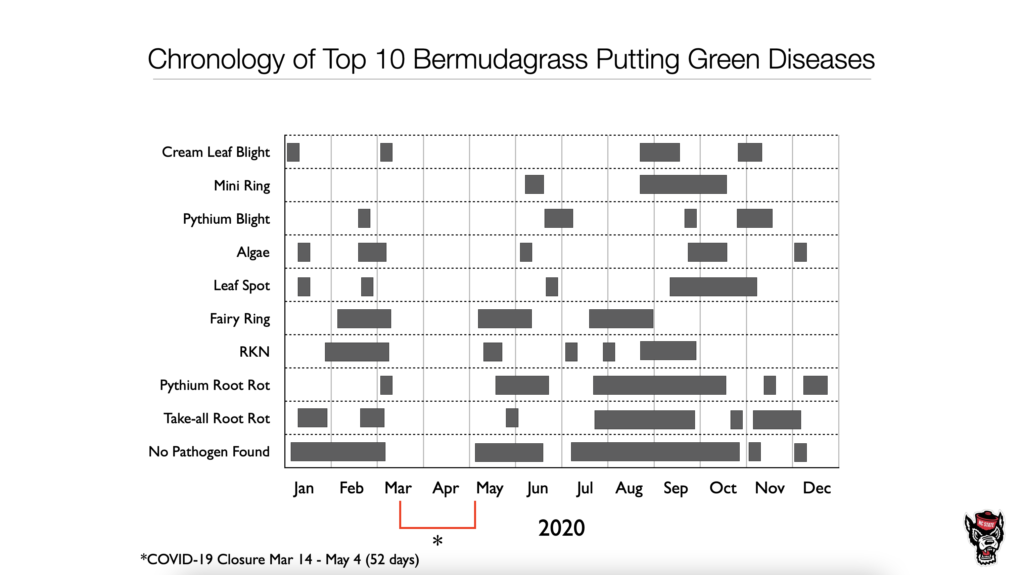

TARR and Pythium Root Rot were the top two diagnosed diseases of bermudagrass putting greens in 2020

The Carolinas were “record warmest” for daily lows and “much above average” for precipitation in 2020.

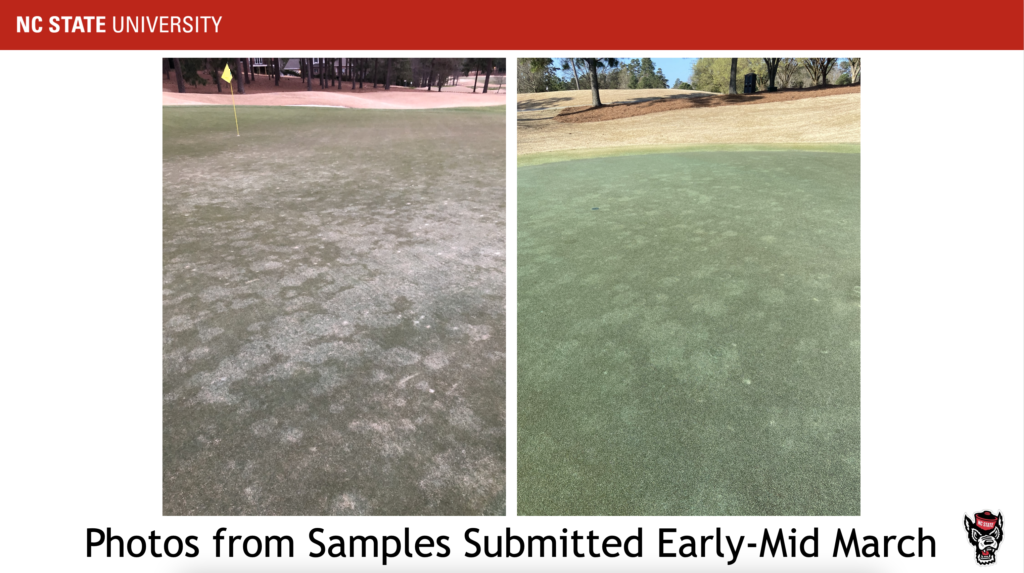

Right now, we are receiving numerous samples exhibiting off-white patches that range in diameter from 6 to 10 inches. We are able to find some evidence of TARR pathogens in the samples, but the colonization is not as severe as when we observe TARR in the fall. No other pathogens have been observed in these samples. Given the weather conditions in the fall and the limited colonization of stolons, rhizomes and roots currently, we hypothesize that most of the damage occurred in the fall and the cooler January and February are causing these patches. Also, keep in mind that the pandemic initiated a surge in golfer participation so increased traffic is also another factor in why these symptoms are developing right now.

Spring symptoms of TARR as bermudagrass putting greens begin waking up from dormancy. Note, smallish off-white patches are common this time of year.

As with 2020, we are starting to see expression of TARR damage in late winter/early spring of the year even though the damage was done the prior summer/fall.

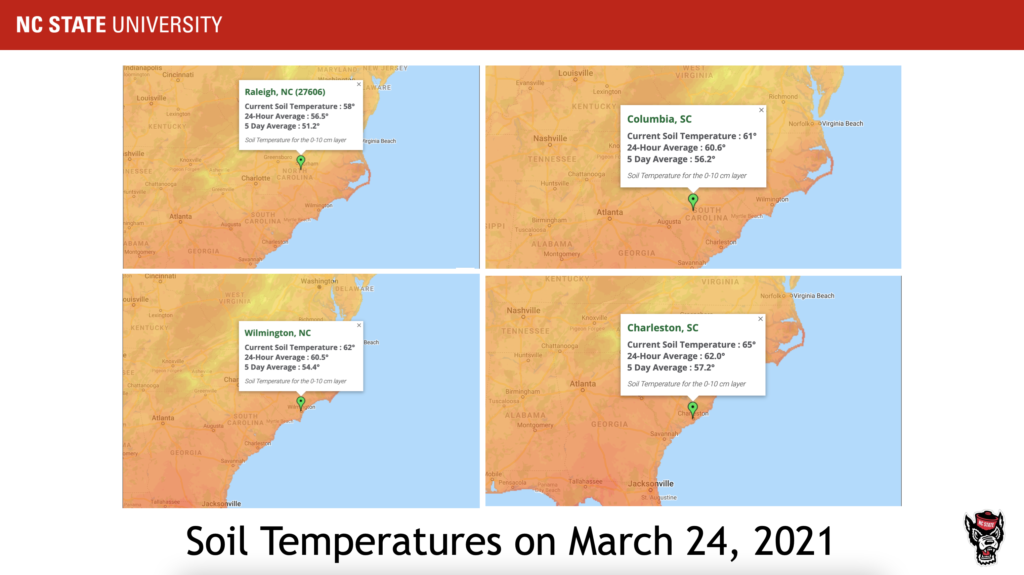

The TARR pathogens grow and infect bermudagrass when soil temperatures are between 86 and 68F from late summer through the fall. Right now, with the current soil temperatures in the Carolinas between these fungi are likely not active, so fungicides may not improve recovery of areas that are affected. Although this may not be what you want to hear, yet fungicides may be warranted to protect the compromised tissue from secondary pathogens. Consider venting and applying nitrogen to improve recovery from TARR damage.

Based on the current soil temperatures, bermudagrass is just barely waking up throughout our region. Although some areas may be “greener”, the plants are not vibrantly growing. The good news is, in the majority of these samples, the stolons were very healthy looking and recovery should happen quickly as soil temperatures warm up.